Mr. Brackenbury

Scenes in the little cellar

Destruction of our home

Another moonlight night with a difference

Reopening of the attack on the Residency

Death of Mr. Brackenbury

Preparations to escape.

Scenes in the little cellar

Destruction of our home

Another moonlight night with a difference

Reopening of the attack on the Residency

Death of Mr. Brackenbury

Preparations to escape.

I REMAINED where he had left me, alone for some minutes, though some of the officers were standing just outside the door of the cellar where I was sitting. It seemed so hard that I could not go with my husband. I feared being left alone without him, and felt very lonely and broken-hearted among so many men, mostly strangers to me. I knew, too, that they would look upon me as an extra burden, and wish me very far away.

I was roused to action by the doctor, who had taken advantage of the truce to get his wounded brought up from the hospital to the house, and had come up first to see what kind of a place could be got ready. I showed him the cellars, for there were several, which all communicated with each other, and formed the entire basement of the house.

Shortly afterwards the Kahars16 arrived, carrying poor Mr. Brackenbury on a mattress, and the others followed fast, so that the small cellar was very soon quite full of men lying side by side on the stone floor. The blankets and sheets that we had already collected were very useful, and I made several journeys up to the house, and gathered up every kind of covering from every direction, and all the pillows I could find. A little cooking-stove proved of great service. I fixed it securely upon a table in one corner which I reserved for cooking operations.

The soup we had made on the previous day was in great request. Fortunately there was a large quantity of it, to which I added the contents of five or six tins which I found in the store-room. Milk was the difficulty. All the cows were out in the grounds, and many of them had strayed away altogether and we could not get any milk from them, so were obliged to fall back on condensed milk, of which we also had several tins.

Some of the men were terribly wounded, but poor Mr. Brackenbury was by far the worst. His legs and arms were all broken, and he had several other injuries besides. It seemed a marvel that he was still alive and fully conscious to all that was going on around him. The doctor attended to him first of all, and had bound up his broken limbs, and done as much as possible to alleviate his sufferings; but it was a terrible sight to see the poor lad in such agony, and be so powerless to lessen it in any way. He was very thirsty, and drank a good deal of soup and milk, but we could not get him into a comfortable position. One minute he would lie down, and the next beg to be lifted up; and every now and then his ankle would commence bleeding, and cause him agony to have it bound up afresh. His face was gray and drawn, and damp dews collected on his forehead from the great pain he was suffering.

That scene will never be forgotten – the little cellar with a low roof, and the faces of the wounded lying together on the floor. We did not dare have a bright light for fear of attracting attention to that particular spot, and the doctor did his work with one dim lantern. Such work as it was, too! Every now and then he asked me to go outside for a few moments while the dead were removed to give a little more space for the living.

There were some terrible sights in the cellar that night – I pray I may never see any more like them; but being able to help the doctor was a great blessing to me, as it occupied my attention, and gave me no time to think of all the terrible events of the day, and the wreck of our pretty home. I was very weary, too – in fact, we all were – and when at about half-past ten I asked everybody to come and get some sort of a dinner, they seemed much more inclined to go to sleep, and no one ate much.

The dinner was not inviting, but it was the best that could be got under the circumstances, for I had had to do it all myself. One or two of the servants still remained, but they cowered down in corners of the house, and refused to move out or help me at all. Perhaps had we known that it was our last meal for nearly forty-eight hours, we should have taken care to make the most of it; but no thought of what was coming entered our minds, and long before the melancholy meal was ended most of the officers were dozing, and I felt as though I could sleep for a week without waking.

We all separated after dinner about the house. I went back to the hospital for a little, and found the doctor wanted more milk, so I returned to the dining-room, where I was joined by Captain Boileau, and we sat there for some time mixing the condensed milk with water, and filling bottles with it, which I took downstairs. It was quieter there than it had been. The wounded had all been attended to, and most of them had fallen asleep. Even Mr. Brackenbury was dozing, and seemed a little easier, and only one man was crying out and moaning, and he was mortally wounded in the head. So finding I could do no more there, I went upstairs again, resolving, if possible, to go to my room and lie down for a little while and sleep, for I was very tired.

I went sorrowfully through our once pretty drawing-room, where everything was now in the wildest confusion, and saw all the destruction which had overtaken my most cherished possessions. There are those who imagine that in a case like this a woman's resource would be tears; but I felt I could not weep then. I was overwhelmed at the terrible fate which had come upon us, and too stunned to realize and bewail our misfortunes.

Perhaps the great weariness which overcame me may have helped me to look passively on my surroundings, and I walked through the house as one in a dream, longing only to get to some haven of rest, where I could forget the misery of it all in sleep.

I wended my way to the bedroom through a small office of my husband's, but when I reached the door I found it would not open, and discovered that part of the roof had fallen in, caused by the bursting of a shell. So I gave up the idea of seeking rest there, and retired to the veranda.

I went down the steps and stood outside in the moonlight for a few minutes. It was a lovely night, clear and bright as day! One could scarcely imagine a more peaceful scene. The house had been greatly damaged, but that was not apparent in the moonlight, and the front had escaped the shells which had gone through the roof and burst all round at the back. The roses and heliotrope smelt heavy in the night air, and a cricket or two chirped merrily as usual in the creepers on the walls.

I thought of the night before, and of how my husband and I had walked together up and down in the moonlight, talking of what the day was to bring, and how little he had thought of such a terrible ending; and I remembered that poor lad lying wounded in the cellar below now, who only twenty-four hours ago had been the life and soul of the party, singing comic songs with his banjo, and looking forward eagerly to the chances of fighting that might be his when the morning came.

I wondered where my husband was, and why they had been away so long. They would be hungry and tired, I thought, and might have waited to arrange matters till the next day, as they had apparently been successful in restoring peace. I had an idea of wandering as far as the gate to see whether the party was visible, but on second thoughts I went back into the veranda, and resolved to wait there until my husband should return.

There was one of the officers asleep in a chair close to me, and I was about to follow his example, when Captain Boileau came out, and I went to him and asked him if he would mind going down to the gate and finding out whether he could hear or see anything of the Chief Commissioner's party, and if he came across any of them to say I wanted my husband. He went off at once, and I fell into a doze in the chair.

It was about twelve o'clock at this time. I do not know how long I had been asleep, when I was awaked suddenly by hearing the deafening boom of the big guns again, and knew then that it was not to be peace.

For a few seconds I could not stir. Terror seemed to have seized hold of me, and my limbs refused to move; but in a minute I recovered, and ran through the house down to the cellar again, where everyone had become alive to the fact that all was over for us. Where was my husband? What had become of them all? This thought nearly drove me mad with anxiety. I could not imagine what their fate had been, but I knew the anguish of mind my husband would endure when the sound of those terrible guns would tell him that we were being attacked again, as he knew we were almost powerless to make any resistance, through lack of ammunition.

We knew that our one chance lay in retreating, as that move had been meditated by Colonel Skene early in the evening, before the truce had taken place; so after an hour had gone by the doctor began moving the wounded out of the. cellar, as an immediate retreat had been decided upon.

We were still without any definite tidings of the position of Mr. Quinton and my husband, and the other officers who had accompanied them, and our anxiety on their behalf increased every hour.

It took a long time to get all the wounded on to the grass outside. Mr. Brackenbury was moved first. Poor lad! he begged so hard to be left in peace where he was, and the moving caused him terrible agony. One by one all the poor fellows were helped out. until only a few remained. I gave my arm to one of these, and we were going out through the cellar door, when we were met by four Kahars, carrying someone back into the hospital. The moonlight shone down upon them as they came, and lit up the white face of him they carried, and I saw that it was Mr. Brackenbury. The movement had killed him, and he had died on the grass outside a few seconds after leaving the cellar. Better thus than if he had lived a few hours longer to bear the pain and torture of our terrible march; but it made one's heart ache to leave that young lad lying there dead, alone in the darkened cellar. I went back there just before we left the place, and covered him up gently with a sheet that was lying on the ground, and I almost envied him, wrapped in the calm slumber of death, which had taken all pain and suffering away.

I had no hope that we should ever succeed in making our escape, and it seemed almost useless even to make the attempt. All was ready, however, by this time for our departure, and I went out too, hoping that the Manipuris would soon set fire to the house, which would prevent any indignities being heaped upon the dead by their victorious enemies.

|

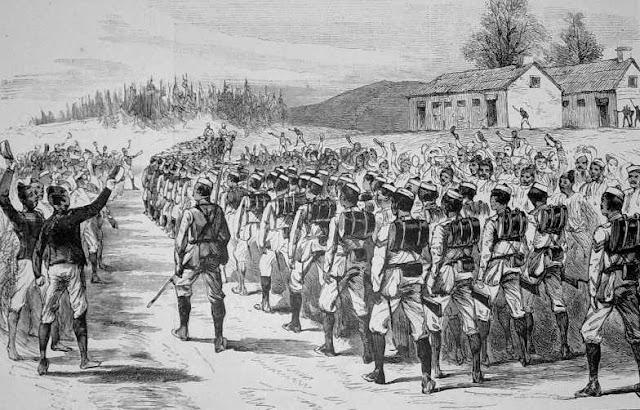

| A French depiction of the attack on the residency |

Outside the noise was deafening. Shells burst around us at every turn, and kept striking the trees and knocking off great branches. All idea of going up into the house had to be abandoned, so I could not get a hat or cloak or anything for the journey before us, and had to start as I was. Just before lunch-time I had taken off the close-fitting winter gown which I had put on in the morning, and instead had arrayed myself in a blue serge skirt and white silk blouse, which gave me more freedom for my work in the hospital. I could not have chosen better as far as a walking costume went, and should have been all right if only I had been able to collect a few outdoor garments – hat, cloak, and boots, for instance. As things happened, I was wearing on my feet thin patent leather slippers, which were never meant for out-of-door use, and my stockings were the ordinary flimsy kind that women generally wear. My dress had got soiled already in the hospital, and was not improved by the march afterwards; but I managed to get it washed when we eventually reached British territory, and have it by me to this day. It will be preserved as an interesting relic.