Our ignorance as to Mr. Quinton's proceedings

News at last reach India and England

Take off my clothes for the first time for ten days

March to Lahkipur

The ladies of Cachar send clothes to me

Write home

Great kindness shown to me

My fears for my husband

The telegram arrives with fatal news

Major Grant's narrative.

News at last reach India and England

Take off my clothes for the first time for ten days

March to Lahkipur

The ladies of Cachar send clothes to me

Write home

Great kindness shown to me

My fears for my husband

The telegram arrives with fatal news

Major Grant's narrative.

DURING the eventful days which had elapsed between March 23 and April 1, nothing definite had been known by the authorities in India as to Mr. Quinton's proceedings and whereabouts. All that was certain was that he had arrived at Manipur, and had been unable to carry out his original plans for leaving again the day following his arrival, owing to the refusal of the Jubraj to obey the orders of Government; but the tidings of the fight which had followed had never been despatched to head-quarters, owing to the telegraph-wire having been cut immediately after the contest began.

That communication, in this manner, was interrupted was not as serious an omen as might have been supposed. Cutting the telegraph-wire was a favourite amusement of the Manipuris; and even during the small revolution in September, 1890, they had demolished the line in two or three directions.

But when several days went by, and still the wire remained broken, and no information of any kind as to what was going on in Manipur reached the authorities, people became alarmed.

Rumours came down through the natives that there was trouble up there; and a few of the traders found their way into Kohima with the news that all had been killed

Then excitement rose high, and every day fresh rumours reached the frontier, some of which said that I and one or two others had escaped, but the rest were either killed or prisoners.

The first definite information came from our party. An officer was sent on by double marches on the 31st with the despatches, civil and military; and before another day had passed the whole of India knew the names of those who had escaped, as well as of those who were prisoners, and in a few hours the news had reached England.

To some, that news must have been snatched up with great relief; but there were many who read it with terrible misgivings in their hearts for the fate of those dear to them who were in captivity.

A person who does not know the sensation of never taking his or her clothes off for ten days can scarcely realize what my feelings were when, on arriving at the Jhiri rest-house, I found a bath and a furnished room. Nothing could ever equal the pleasure which I derived from that, my first tub for ten days. I felt as though I should like to remain in it for hours; and even though I had to array myself again afterwards in my travel-stained and ragged garments until I reached Lahkipur, the sensation of feeling clean once more was truly delightful.

I was covered with leech-bites, and found one or two of those creatures on me when I took off my clothes. They had been there three or four days, for we had fallen in with a swarm of them at one of the places where we had camped for the night during the march. It was near a river and very damp, and the leeches came out in crowds and attacked everybody. But the men were able to get rid of them better than I was, and I had to endure their attentions as best I might until we got to the Jhiri, and I could indulge in the luxury of taking off my clothes.

I slept on a bed that night, and was very loath to get up when the bugle awoke us all at the first streak of dawn.

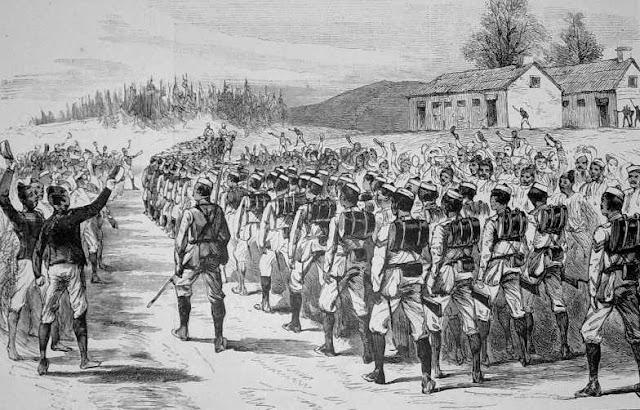

We marched ten miles into a place called Lahkipur, where we found a number of troops already mustering to return to Manipur.

I found clothes and many other necessaries at Lahkipur, which had been sent out for me by the ladies of Cachar; and I blessed them for their thoughtfulness.

The luxury of getting into clean garments was enchanting; and though the clothes did not fit me with that grace and elegance that we womenkind as a rule aspire to, still, they seemed to me more beautiful than any garments I had ever possessed. They were clean; that was the greatest charm in my eyes.

Then came breakfast, such as we had not indulged in for a very long time, and everything seemed delicious.

Immediately after breakfast we all sat down to write home. It was hard work for me after all I had gone through, and with the keen anxiety I was still feeling about those left behind, to put the account of the terrible disaster into words; but I felt that if I did not write then, I should not have the strength to do so later on, and I managed to send a full account home by the next mail.

We halted at Lahkipur all that day, and we started to march our last fourteen miles into Cachar on the night of April 2, or, rather, the early morning of the 3rd. A number of the planters in the neighbourhood came in to Lahkipur to see us before we left, and hear from our own lips the narrative of our escape, and the news of it all got into Cachar long before we ourselves arrived.

Everyone seemed anxious to show us all kindness; but the efforts that were made to secure comforts for me in particular were innumerable as they were generous. When I eventually did arrive at Cachar, I found myself made quite a heroine of. There was not one who did not seem honestly and heartily glad to see me there again safe, and I shall never forget the kindness I received as long as I live.

But amongst them all, there were some old friends who received me into their house, putting themselves out in every possible way to add to my comfort, to whom I owe a debt of gratitude that I never can repay. It would not perhaps be quite agreeable to them if I wrote their names here; but when this record of my terrible adventure reaches them in their far-off Indian home, they will know that I have not missed the opportunity, which is given me in writing about it, of paying them a tribute of gratitude and affection for all their goodness to me in a time of great trouble.

It was delightful to have a woman to talk to again, although my companions on the march had one and all shown me how unselfish and kindhearted Englishmen can be when they are put to the test. They had never let me feel that I was a burden on them, and though often I felt very weak and cowardly, they quieted my misgivings, and praised me for anything I did, so that it gave me courage to go on and help to endure the horrors of that terrible retreat.

For a week I remained with my friends at Cachar, tormented by anxiety concerning my husband, The general opinion seemed to be that he and his companions would be perfectly safe, but I was full of terrible misgivings. I remembered stories of the Mutiny in bygone days, and had read how the prisoners then had often been murdered just at the moment when rescue was at hand.

I feared that when the troops should go back, the Jubraj would refuse to make terms with them, and would threaten to kill the prisoners if our troops came into the place, and I wondered what they would do in that case.

I sent two letters up by Manipuris to my husband, care of the regent, telling him of my escape. I was only allowed to write on condition that I said nothing of the preparations which were being made to rescue Mr. Quinton and his party. But it was a relief to me to be able to write a few lines, for my one idea was to spare my husband the awful anxiety which he would endure until he should hear of my safety.

I had been a week in Cachar when the news came which put an end alike to all hope and all fear. Troops had been hurrying back to Manipur, and the station was alive with Sepoys of all regiments. All the officers and men who had come down with me from Manipur had gone some way on the road back there. The wounded had been placed in the Cachar hospital, where I went to see them two or three times. Poor little fellows! they all seemed so glad to see me.

At last one evening, exactly a week after our arrival, a telegram arrived from Shillong to say that authentic news had come from the regent at Manipur to the effect that all the prisoners had been murdered. I saw the telegram arrive. I was in the deputy commissioner's bungalow when it was handed to him, and made the remark that I disliked bright yellow telegrams, as they always meant bad news.

In India a very urgent message is always enclosed in a brilliant yellow envelope. But the officer said that he did not think anything of them, as he was receiving so many of them at all hours of the day, and for the time I thought no more about it.

Shortly afterwards I noticed that he had left the table. Then I went out too, and met my friend outside, who seemed rather upset about something, and told me she was going home at once. So we went together.

But as soon as we had got into the house she broke to me, as gently and mercifully as she could, the news that my husband had been killed. It was a hard task for her, and the tears stood in her eyes almost before she had summoned up the courage to tell me the worst. And when she had told me I could not understand. The blow was too heavy, and I felt stunned and wholly unable to realize what it all meant. I could not believe, either, that the news was true, for it seemed to me impossible that any authentic intelligence could have been received.

|

| Frank Grimwood is speared by Kajao Pukhramba Phingang |

But after a night of misery, made almost heavier to bear by reason of the glimmer of hope which still remained that the news might be false, the morning brought particulars confirming the first message, and giving details which put an end to any uncertainty. The regent had sent a letter saying that the prisoners had been killed. I believe he stated they had fallen in the fight at first, but afterwards contradicted himself, and said they had been murdered by his brother, the Jubraj, without his knowledge or consent. I cannot dwell on this part of the story. It is all too recent and painful as yet, and too vivid in my recollection. There are no words that can describe a tragedy such as this. Besides, the fate of those captives is no unknown story. All know that through treachery they found themselves suddenly surrounded by their enemies, with all hope of help gone, and without the means to defend themselves.

And the ending – how they were led out one by one in the moonlight to suffer execution, after having been obliged to endure the indignity of being fettered! How, of that small band, one had already fallen dead, speared by a man in the crowd; and one was so badly wounded that he had fallen, too, by the side of his dead friend, and had to be supported by his enemies when he went out, as the others had to go, to meet his fate.

|

| A contemporary Indian illustration of the murder of Quinton, Cossins, Col. Skene & Lieut. Simpson between the Kangla Sha dragons, March 1891. (Grimwood had been murdered prior to this event) |

And yet in all that terrible story there is one ray of comfort for me in the fact that my husband was spared the fate of the rest. I am glad to think that he did not suffer. He never heard those terrible guns booming out, proclaiming the work of destruction which was being wrought on the home he had loved. He did not see the cruel flames which reduced our pretty house to a heap of smoking ruins, and he did not know that I was flying for my life, enduring privations of every kind, lonely, wretched, and weary at the outset.

He was spared all this, and I am thankful that it was so. For before the guns commenced shelling us again on that dreadful night, the tragedy described had already taken place within the palace enclosure.

Well for me was it that I was ignorant of my husband's fate. Had I known, when we left the Residency that night, that he and I were never to meet again on God's earth, I could never have faced that march. It had been hard enough as it was to go and leave him behind me; but thinking that he was safe helped me in the endeavour to preserve my own life for his sake.

It is time to end this narrative of my own experiences, for all was changed for me from the day that brought the terrible news; but the account of the incidents of March, 1891, would scarcely be complete without my touching on some other events which were occurring in a different quarter in connection with the Manipur rebellion.

I allude to the noble part taken by Mr. Grant (whom I have referred to earlier in this volume) in the affair as soon as tidings of the disturbance reached him. To describe his share in my own words would scarcely be a satisfactory proceeding, so I have thought it better to add his letter, giving all the details of what occurred, to my own narrative.

The news first reached him on the morning of March 27, and in his letters home he describes the subsequent events as follows:

'On March 27, morning, thirty-five men of 43rd Ghoorka Light Infantry came into Tummu, reporting there had been a great fight at Manipur on 25th. Chief Commissioner Grimwood, the Resident, same who came to see me with wife, Colonel Skene, and many others, killed, and five hundred Ghoorkas killed, prisoners, or fled to Assam; the thirty-five men of 43rd Light Infantry had been left at the station Langthabal, four miles south of Manipur, and after the others broke they retreated to Tummu in forty-eight hours, only halting four hours or so, fighting all the way and losing several killed. I wired all over Burmah, and asked for leave to go up and help Mrs. Grimwood and rest to escape, and got orders at eleven p.m. on 27th.

'At five a.m., 28th, I started with fifty of my men, one hundred and sixty rounds each, thirty Ghoorkas, Martini rifles, sixty rounds, and three elephants; marched till five p.m., then slept till one a.m., 29th, marched till two p.m., slept till eleven p.m., marched and fought all the way till we reached Palel at seven a.m., 30th, having driven one hundred and fifty men out of a hill entrenchment and two hundred out of Palel, at the foot of the hills, without loss. Elephants could only go one mile or so an hour over these hills, 6,000 feet high, between this and Tummu, but road very good. Prisoners taken at Palel said that all the Sahibs killed or escaped; Mrs. Grimwood escaped to Assam. Poor Melville, who had stayed a week before with me at Tummu (telegraph superintendent), killed on march.

'I marched at eleven p.m., 30th, and neared Thobal at seven a.m., meeting slight resistance till within 300 yards of river, three feet to six feet deep, and fifty yards broad; there seeing a burning bridge, I galloped up on poor "Clinker" (the old steeplechasing Burman tal I had just bought on selling my Australian mare "Lady Alice"), and was greeted by a hot fire from mud-walled compounds on left of bridge and trenches on the right in open all across the river. I saw the wooden bridge was burnt through, and made record-time back to my men, emptying my revolver into the enemy behind the walls.

'My men were in fighting formation. Ten my men 2nd Burmah Battalion of Punjaub Infantry (new name), and ten Ghoorkas in firing line at six paces interval between each man, and twenty my men in support 100 yards rear of flanks in single rank, and twenty my men and twenty Ghoorkas reserve, baggage guard 300 yards in rear with elephants, and thirty followers of the Ghoorkas (Khasias, from Shillong Hills). We opened volleys by sections (ten men) and then advanced, one section firing a volley while the other rushed forward thirty paces, threw themselves down on ground, and fired a volley, on which the other section did likewise. Thus we reached 100 yards from the enemy, where we lay for about five minutes, firing at the only thing we could see, puffs of smoke from the enemy's loopholes, and covered with the dust of their bullets. I had seen one man clean killed at my side, and had felt a sharp flick under arm, and began to think we were in for about as much as we could manage; but the men were behaving splendidly, firing carefully and well directed. I signalled the supports to come up wide on each flank; they came with a splendid rush and never stopped on joining the firing line, but went clean on to the bank of the river, within sixty yards of the enemy, lying down and firing at their heads, which could now be seen as they raised them to fire; then the former firing line jumped up and we rushed into the water. I was first in, but not first out, as I got in up to my neck and had to be helped out and got across nearer to the bridge, the men fixing bayonets in the water.

'The enemy now gave way and ran away all along, but we bayoneted eight in the trenches on the right, found six shot through the head behind the compound wall. At the second line of walls they tried to rally, but our men on the right soon changed their minds, and on they went and never stopped till they got behind the hills on the top of the map; our advance and their retreat was just as if you rolled one ruler after another up the page on which the map is.

'When I got to (A) I halted in sheer amazement; the enemy's line was over a mile long. I estimated them at eight hundred, the subadar at one thousand two hundred; afterwards heard they were eight hundred men besides officers. They were dressed mostly in white jackets with white turbans and dhoties, armed with Tower-muskets, Enfield and Snider rifles, and about two hundred in red jackets and white turbans, armed with Martinis, a rifle that will shoot over twice as far as our Sniders. I simply dared not pursue beyond (A), as my baggage was behind, and beyond them I had seen two or three hundred soldiers half a mile away on my right rear.

'At eight a.m. I was in the three lines of compounds, each compound containing a good house about thirty by twenty feet (one room), and three or five sheds and a paddy-house. We carried over our baggage on our heads, leaving a strong party at (A), and set to work to prepare our position for defence. I had used eighty of our one hundred and sixty rounds per man; only one man was killed. I found I was slightly grazed, no damage, and three of my six days' rations; and I could not hope to reach Manipur, therefore I must sit tight till reinforced from Burmah, or joined by any of the defeated Ghoorka Light Infantry troops from Cachar.

'We filled the paddy-house with paddy, about a ton, and collected much goor (sugar-cane juice) and a little rice and green dhal and peas from the adjoining houses. Then I cleared my field of fire – i.e., by cutting down the hedges near and burning the surrounding houses and grass; my walls were from two feet to four feet high, and one to three feet thick, and, I thought, enough. Put men on half ata and dhal; shot a mallard (wild duck on river), and spent a quiet night with strong pickets.

'On April 1, at six a.m., my patrols reported enemy advancing in full force from their new position. I went to (A), where picket was, and took a single shot with a Ghoorka's Martini into a group of ten or twelve at 700 yards. The group bolted behind the walls at (B), and the little Ghoorkas screamed with delight at a white heap left on the road, which got up and fell down again once or twice, none of the others venturing out to help the poor wretch.

'Then a group assembled on the hill, 1,000 or 1,100 yards off, and the Ghoorka Jemadar fired, and one went rolling down the hill; I fired again, but no visible effect. The enemy then retired under cover; but at three p.m. they advanced in full force. I lined wall (A) with fifty men, holding rest in reserve in the fort.

'The enemy advanced to 600 yards, when we opened volleys, and after firing at us wildly for half an hour, they again retired to 800 yards, and suddenly from the hill a great "boom," a scream through the air; then, fifty feet over our heads, a large white cloud of smoke, a loud report, and fragments of a 9-lb. or 10-lb. elongated common shell from a rifle cannon fell between us and our fort; a second followed from another gun, and burst on our right; then another struck the ground and burst on impact to our front, firing a patch of grass; they went on with shrapnel.

'I confess I was in a horrid funk, for although I knew that artillery has little or no effect on extended troops behind a little cover, I dreaded the moral effect on my recruits, who must have had an enormously exaggerated idea of the powers of guns; but they behaved splendidly, and soon I had the exact range of the guns, by the smoke and report trick, 900 or 970 yards; and after half an hour, during which their fire got wilder and wilder, both guns disappeared, and only one turned up on the further hill, 1,500 yards from (A), from which they made poor practice, as the Ghoorkas' bullets still reached them, and they only ran the gun up to fire, and feared to lay it carefully. All this time the enemy kept up their rifle fire, from 600 to 800 yards, but I only replied to it when they tried to advance nearer.

'By this time it grew dark, and when we could no longer see the enemy we concentrated in the fort, as the enemy had been seen working round to our left. I sent the men back one by one along the hedges, telling each man when and where to go; none of them doubled.

'It was quite dark when I got back, and posted them round our walls, which seemed so strong in the morning, but were like paper against well-laid field-guns; I felt very, very bitter.

'I was proud of the result of my personal musketry-training of my butchas (children), all eight months' recruits, except ten or fifteen old soldiers, who set a splendid example, and talked of what skunks the Manipuris were, compared to the men they had fought in Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier; but they all said they had never seen such odds against them before. Our total day's loss – a pony killed, and one man slightly wounded.

'All night the enemy kept up a long-range fire without result, which was not replied to, I tied white rags round our foresights for night-firing. I slept for about two hours in my east corner, and at three a.m. turned out to strengthen the walls in four places against shell-fire, made a covered way to the water, and dug places for cover for followers. Luckily much of the compound was fresh ploughed, so we only had to fill the huge rice-baskets with the clods, and the ration-sacks, pails, my pillow-case, and a post-bag I had recovered, everything with earth, and soon I had five parapets in front and flanks, each giving cover for eight or ten men. The enemy had retired behind the hill.

'At three p.m. a patrol reported a man flag-signalling. I went out with white flag, and met a Ghoorka of 44th, a prisoner in Manipuris' hands, who brought a letter signed by six or eight Babu prisoners, clerks, writers, post and telegraph men, saying there were fifty Ghoorka prisoners and fifty-eight civil prisoners, and imploring me to retire. If I advanced they would kill the prisoners; if I retired the durbar would release them, and send them to Cachar. I said those prisoners who wished could go to Cachar, and I would retire to Tammu with those who wished to come with me.

'I also wrote to the Maharajah, and also on 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th messages passed from me to Maharajah and his two brothers, Jubraj and Senaputti, the heir and the commander-in-chief.

'Maharajah wrote saying he was not responsible for the outbreak; and Senaputti told the messengers he had 3,000 men in front of me, and would cut us all up.

'I wrote refusing to move without the Ghoorka prisoners at least, and said "I didn't care for 5,000 Manipuri Babus." 23

'At last Jubraj said the prisoners had been sent away to Assam, and sent me 500 pounds ata and 50 pounds each dhal and ghee to retire with. I sent back the rations, and refused to move without a member of the durbar as a hostage, to remain at Tammu till prisoners arrived at Cachar and Kohima. They offered me a subadar. I said he was no one. I had signed all my letters as Col. A. Howlett, Com. 2nd B. Regt., to impress them with my strength and importance, and put on the subadar's badges of rank in addition to my own.

'The next morning (6th) they attacked again at dawn, and as I had only seventy rounds per man for Sniders and thirty for Martinis, I closed into the fort. At first, after forty minutes' shelling, they made determined efforts to cross the walls 100 to 200 yards in front of my front and left; but nearly every man was hit as he mounted the wall, and then they remained firing from behind the walls.

'At eight a.m. a good lot had collected behind the wall 200 yards from my left. I crept out with ten or twelve Ghoorkas, who held my rear and right under the hedge, and drove them with loss by an attack on their right flank, and we bolted back to fort without loss.

'Then at eleven a.m. there was firing from behind the hedges to our front with a weapon that rang out louder than their rifles. I crept out with a havildar and six Ghoorkas close in the ditch under the hedge, out to our front from our right, up to within ten yards of the nearest of them. They opened a wild fire, and bolted as we attacked their left flank; but then we found ourselves in a bit of a hole, for thirty or forty were in a corner behind a wall, six feet high, over which they were firing at us. I had my D. B. sixteen-bore shot-gun, and six buckshot and six ball cartridges, and as they showed their heads over the wall they got buckshot in their faces at twenty yards.

'When my twelve rounds were fired, and the Ghoorkas also doing considerable damage, we rushed the wall, and I dropped one through the head with my revolver, and hit some more as they bolted.

'When we cleared them out we returned to the fort along the ditch, having had the hottest three minutes on record, and only got the Ghoorka havildar shot through the hand and some of our clothes shot through; we had killed at least ten.

'Next day I visited the corner, and found blood, thirty Snider and fifteen Martini cartridges, and one four-inch long Express cartridge, '500, which accounted for the unaccountable sounds I had heard.

'Next day I heard I had killed the "Bhudda" (old) Senaputti, or the commander-in-chief of the old Maharaj, father of the present lot of scoundrels, and also two generals; but that is not yet confirmed.

'Well, as I said, we bolted back into the fort, and I had thirty minutes' leisure to go all round my fort, and found I had only fifty rounds per man, enough for one hour's hard fighting, and only twenty-five for Martinis; so I ordered all the men to lie down behind the walls, and one man in six kept half an hour's watch on their movements. The men had orders not to fire a shot till the enemy were half-way across the open adjoining compounds; but the enemy declined to cross the open, and the men did not fire a shot all day. I picked off a few who showed their heads from the east corner, where I spent the rest of the day, the men smoking and chatting, and at last took no notice of the bullets cutting the trees a foot or six inches over their heads.

'Thus the day passed, the enemy retiring at dark, and we counted our loss – two men and one follower wounded, one by shell; one pony killed, two wounded; two elephants wounded, one severely; and my breakfast spoilt by a shell, which did not frighten my boy, who brought me the head of the shrapnel which did the mischief – I will send it home to be made into an inkpot, with inscription – and half my house knocked down.

'Next day, 7th, quiet, improved post and pounded dhan to make rice.

'Saturday, 8th, ditto. Large bodies of Manipuris seen moving to my right rear long way off.

'At five, 7th, two Burmans came with letters from Maharajah to Viceroy, and a letter from "civil" to poor killed chief commissioner. I opened and found that large army comes up from Burmah "at once." A small party three or four days before would have been more use. Maharajah's letter a tissue of miserable lies and stupid excuses.

'At noon, 8th, white flag appeared, and a man stuck a letter on road and went back. Went and found it contained a letter from Presgrave, with orders from Burmah for me to retire on first opportunity, and he was not to reinforce me, but to help me to retire. I was sick, but the orders were most peremptorily worded. So at 7.30 p.m., on a pitch-dark, rainy night, we started back – a splendid night for a retreat, but such a ghastly, awful job!

'We had two wounded elephants with us, and made just a mile an hour, only seeing our hands before our faces by the lightning-flashes. I had to hold on to a Sepoy's coat, as I could see absolutely nothing; but they see better in the dark than we do. We were drenched to the skin, and were halting, taking ten paces forward when the lightning flashed, and then halting the column half an hour at times; but the feeble Manipuri, of course, would not be out such a night, and we passed through three or four villages full of troops without a man showing.

'At two a.m., 9th, a man said sleepily, "The party has come" – that was all – and the next moment Presgrave had my hand. He had heard that I was captured, and all my men killed or taken at two different places; had returned nearly to Tummu, but the two Burmans with Maharajah's letter told him where I was, and he marched thirty-six hours without kit or rations, only halting for eight hours, and was coming on to Tummu. He went back to meet some rations, and then, after passing the night in a Naga village, returned to Palel and here, with a hundred and eighty men and eleven boxes of ammunition – forty of them our mounted infantry.

'At Palel we found three or four hundred Manipuri soldiers who did not expect us; they saw us half a mile off, and bolted after firing a few shots. I went on with the mounted infantry, and after trotting till within 300 yards of the retreating army, we formed line on the open and went in.

'I rode for a palki and umbrella I saw, and shooting one or two on my way got close up; but a hundred or so had made for the hills on our right and made a short stand, and suddenly down went poor Clinker on his head, hurling me off. Jumped up – I was covered with blood from a bullet-wound in the poor beast's foreleg, just below the shoulder. Two men came up. I twisted my handkerchief round with a cleaning-rod above the wound, stopping the blood from the severed main artery, and, refilling my revolver, ran on.

'By this time the men had jumped off and were fighting with the enemy on the hill; the palki was down, and I fear the inmate of it escaped. We killed forty of them without loss, excepting poor Clinker and another pony. After pursuing three miles we stopped, and returned to the infantry, which were rather out of it, though they doubled two miles. Found poor Clinker's large bone broken, and had to shoot him at once.

'We collected the spoil and returned to camp, where we had a quiet night, and were joined by the Hon. Major Charles Leslie and four hundred of his 2nd-4th 24 Ghoorkas, and two mountain guns; Cox of ours. Total now, eight British officers; all very nice and jolly; but to our disgust we have to halt here for rest of ours, rest of Ghoorkas, two more guns, and General Graham.

'Cox brought me telegrams of congratulations from Sir Frederick Roberts, General Stewart, commanding Burmah, and Chief Commissioner, saying everything kind and nice they could. I sent in my despatches next day, and so the first act of the Manipur campaign closes.

'My men have behaved splendidly, both in attack, siege, and retreat, and I have recommended all for the Order of Merit, My luck all through has been most marvellous; everything turned up all right, and there was hardly a hitch anywhere. Poor Clinker! He was 300 yards from eight hundred rifles for twenty minutes and never touched, and a shot killed him at full gallop. Now "bus" (enough) about myself in the longest letter I have ever written.'

'Manipur Fort, April 28.

'We arrived here yesterday, and found it empty. We gave them such an awful slating on the 25th that they resisted no more either at my place, Thobal, or here. On the 25th I went out from Palel with fifty my men, Sikhs, fifty our Mounted Infantry under Cox, and fifty 2nd-4th Ghoorkas, the whole under Drury, of 2nd-4th Ghoorkas. We had orders only to reconnoitre enemy's position, not to attack, as remainder were to arrive that morning.

'The road ran along the plain due north towards Manipur, with open plain on left and hills right. Saw the enemy on the hills and in a strong mud fort 1,000 yards from hills in the open. I worked along the hills and drove the enemy out of them, as we found them unexpectedly, and had to fight in spite of orders. Then Drury sent on to the general to say we had them in trap, and would he come out with guns and more men and slate them. Then he sent the Mounted Infantry to the left to the north-west of the enemy, and we worked behind the hills to the north-east, thus cutting them off from Manipur. We went behind a hill and waited.

'At 11.30 we saw from the top of our hill the column from Palel, two mountain guns, and one hundred 2nd-4th Ghoorkas. The guns went to a hill 1,000 yards to the east of the enemy's fort, and we watched the fun. The first shell went plump into the fort; soon they started shrapnel and made lovely practice, the enemy replying with two small guns and rifles. Then we got impatient and advanced, and worked round to their west flank. The guns went on sending common shell and shrapnel into the fort till we masked their fire. The Ghoorkas, also under Carnegy, advanced from south from Palel. We did not fire a shot till within 100 yards, fearful of hitting own men. Then our party charged, but were brought up by a deep ditch under their walls; down and up we scrambled, and when a lot of our men had collected within ten paces of their walls, firing at every head that showed, the enemy put up a white flag, and I at once stopped the fire. Then they sprang up and fired at us. I felt a tremendous blow on the neck, and staggered and fell, luckily on the edge of the ditch, rather under cover; but feeling the wound with my finger, and being able to speak, and feeling no violent flow of blood, I discovered I wasn't dead just yet. So I reloaded my revolver and got up.

'Meanwhile my Sikhs were swarming over the wall. I ran in, and found the enemy bolting at last from the east, and running away towards Manipur. My men were in first, well ahead of both parties of Ghoorkas.

'After I had seen all the Manipuris near the fort polished off, I sent for a dresser and lay down in one of the huts in the fort. Soon had my clothes off, and found the bullet had gone through the root of my neck, just above the shoulder, and carried some of the cloth of my collar and shirt right through the wound, leaving it quite clean. I was soon bound up, and men shampooed me and kept away cramp. It was only a very violent shock, and I felt much better in the evening.

'As soon as the enemy got clear of the fort the shrapnel from the hills opened fire on them, and when they got beyond, then Cox cut in with his mounted infantry, and only five or six escaped; but poor Cox got badly shot by one of them through the shoulder, but is doing well.

'Carnegy and Grant, of the 2nd-4th, found twenty or thirty of the enemy in a deep hole in the corner of the fort, where they had escaped our men, and in settling them Carnegy got shot through the thigh, and Drury got his hand broke by the butt of a gun. Two of my men were wounded, and two of the 2nd-4th killed, and five or six wounded, I think because they were in much closer order than my men, who were at ten paces interval.

'We gathered seventy-five bodies in the fort and fifty-six near it, and the shrapnel and mounted infantry killed over one hundred. The Manipuris here say we killed over four hundred. So we paid off part of our score against their treachery. We spent the night there.

'They were tremendously astonished and disgusted when they heard in Palel we had had such a fight. The fact is we left them no bolt-hole, and they thought, after their treacherous murder of the five Englishmen at Manipur, that we would give them no quarter, and so every man fought till he was killed.

'Next morning we advanced to my fort at Thobal, and found it deserted; and the royal family and army fled from Manipur as soon as they heard of the action of the 25th. So yesterday, the 27th, we marched in here, my Thobal party, by order of the general, being the first to enter the palace on our side, the Cachar and the Kohima columns arriving from the west and north just before them.

'I, alas! in my dholi, did not get up till two hours after, as it poured all the march, and the mud was awful; but I slept last night, and to-day am feeling fit and well.

'General Collett, commanding the army, came to-day to see me, and said all sorts of nice things to me, and his A.-G. asked me when I would be a captain, and said I would not be one long, meaning I would get a brevet majority. But all these people are very excited now, and talk of my getting brevet rank, and V.C. and D.S.O.; but when all is settled, if I get anything at all I will be content, and it will be about as much as I deserve. I have asked leave if I might stick to my men, as they had stuck so well to me at Thobal. I have had such luck, the men in this regiment will do anything for me, and I hate the idea of changing regiments again, so I may remain if a vacancy occurs.

'I went out for a "walk" in my dholi this evening, and went round the palace – a very poor place.'

No comments:

Post a Comment